Article — 7 Min Read

10 things to know about 19th Century European Art

Article — 7 Min Read

10 things you should know about 19th Century European Art

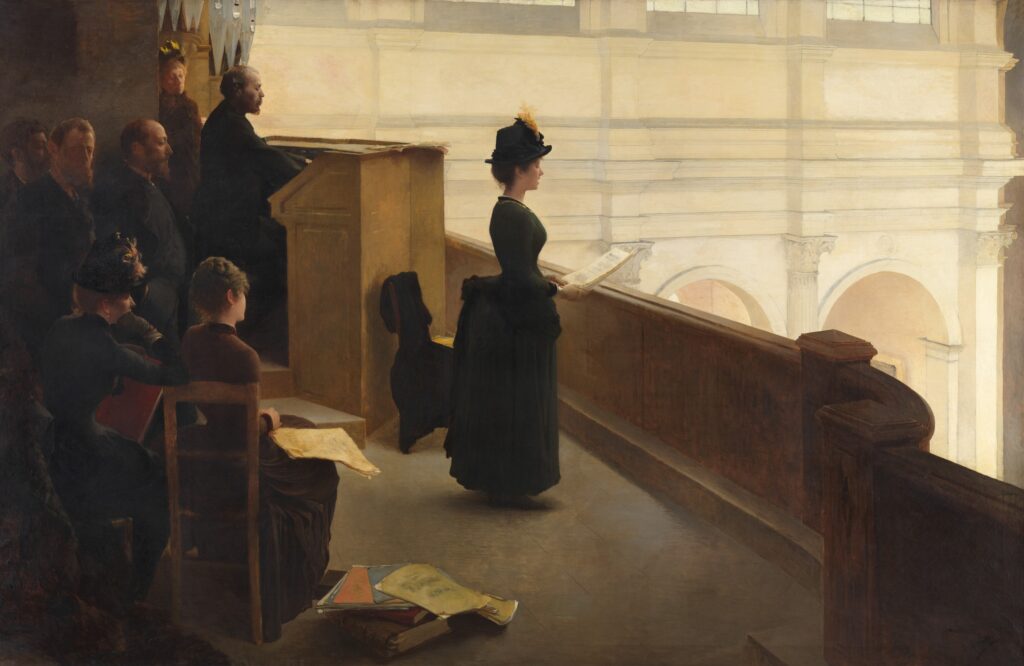

It was an age of revolutions both industrial and political. It was a time for the fall of empires and the rise of new nations, and it saw a great colonial expansion out to every continent in the world. It was the 19th century.

1. Reactions to Industrialisation

19th century art leaves us a legacy of this time, not written in the land with railroad tracks or in the constitutions of parliamentary democracies, but in the innovative techniques and expressive contrasts of some of the greatest artists to ever put paintbrush to canvas.

The key to understanding 19th century art for collectors and art lovers is understanding the social forces at play that changed every facet of life: modern capitalists who sought a steam-powered solution to everything, aristocrats who dreamed of the knights and kings of older days, and a newly formed urban working class who yearned for rights of their own.

Artists reacted and even directly participated in the confrontations between these social forces that shaped the world into what it looks like today.

2. Broader Horizons

One of the key features of 19th century art is the wide variation in subject matter. For hundreds of years previous, artists worked mainly as journeymen, making work commissioned by lords and churches.

This led to plenty of paintings of the crucifixion and portraits of dukes, with the occasional scene from history and classical mythology mixed in. The rococo movement of the 18th century began to break up this monotony with pastel-colored scenes of aristocrats at play, but this only hinted at what was to come.

The 19th century witnessed large numbers of artists who sold their work after painting it, earning the hard coin available in the new galleries and the private collections of a burgeoning middle class. These progressive youngsters were hungry for new subject matter and were finally free to pursue it.

By the 19th century, we start seeing paintings of bathing revelers, peasant folk tales, revolutionary propaganda, and cozy views across the Seine.

3. New Approaches to Painting

With artists always on the lookout for new subject matter, so too came a desire to paint in ways no one ever had before.

European art had been stuck in the clutches of a formalist approach that aped the canon’s masters, an effect of artists working almost entirely on commission for wealthy patrons. But now that more and more artists were working for themselves, they were free to explore not only what they painted but how they painted.

Fueled by increases in the speed of travel, thanks to the railways, artists could also more easily travel around Europe, finding each other in cafes from London to Rome and beyond. They looked at each other’s experiments and made their own steps into new frontiers of style.

What arose were a series of art movements that carried us from the evening of the classical era into the dawn of modern art.

4. Romanticism

Romanticism was an iconic movement in 19th century art, creating new concepts about art and the artist that survive with us even to this day. While beginning in the middle of the 18th century, it reached its height of importance in the first half of the 1800’s.

At its heart, romanticism was a reaction to the industrial revolution. A notable group of artists lamented the changes in the world as smokestacks rose over cities, railroads cut through countryside, and new economic forms pulled peasants from the farm into the cramped, soot-covered squalor of urban centers.

The Romantics favored the creative, irrational impulses of the human heart over the logical order of Enlightenment thinking and scientific materialism. Romantic art, which had sister movements in literature and music, looked to their local folklore and idealized visions of chivalrous knights in the Medieval age for subject matter.

The individual styles of the Romantics could be quite different, but they all wrung as much emotion as they could out of their work. Their work often emphasized the individual and notions of will, man’s relation to God, and the gothic.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) is a masterpiece encapsulating the spirit of individualism and stirring emotion indicative of the Romantic movement.

As national revolutions began to shape the 19th century, many works from the Romantics became important for these political movements — due in large part to their focus on local ethnic cultures. This connection led to what is likely the most celebrated painting in Romantic art, Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) — a mythic portrayal of the French Revolution.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) is a masterpiece encapsulating the spirit of individualism and stirring emotion indicative of the Romantic movement.

As national revolutions began to shape the 19th century, many works from the Romantics became important for these political movements — due in large part to their focus on local ethnic cultures. This connection led to what is likely the most celebrated painting in Romantic art, Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) — a mythic portrayal of the French Revolution.

5. Neoclassicism

On the other side of the art world from Romanticism sits Neo-Classicism. While already a dominant force at the start of the 19th century, it went on to hold an important place in European art for decades.

Neoclassicism was a celebration of the Enlightenment values of rational order as well as the architectural style of the Roman Empire. When the well-preserved sites of Pompeii were uncovered in the 1700’s, artists were inspired by the classical world’s achievements, and they quickly set about replicating them.

Whilst some artists were raging against the cold logic and demystifying science of the age, the Neoclassicists were celebrating humanity’s rational faculties.

Neoclassicists, as you might have guessed, painted many scenes from Greek and Roman mythology and history. Their style involved meticulous attention to balanced composition, high key lighting, and superlative verisimilitude.

The brush stroke and finishing techniques of the Neoclassicists strove for invisibility, as if their works were windows on a scene frozen in time, not the work of a painter applying colored paste onto fabric.

The movement cohered around the achievement of Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784), and it began to appear everywhere. From the design of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia palace of Monticello to Italian sculpture, Neoclassicism became a force in art of all kinds.

It was a good fit for the Age of Reason, exalting the human capacity for intelligently ordering the world.

6. Pre-Raphaelites

In 19th century England, the battle between the heart and mind was also being waged. Fueled by their love of nature and rejection of the suffocating conformity of English art in that period, a group of artists began meeting in secret to plot a new form of art that would change the world forever.

Like a revolutionary cell plotting the overthrow of a king, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood plotted the overthrow of Italian artist Raphael’s (1483-1520) influence on English art. Calling for a return to Renaissance approaches, they wanted to return to the styles pre-dating Raphael, hence their name. The brotherhood first met in 1848, a year of extreme political turmoil on the continent.

Celebrating nature, spiritualism, love, and death, the Pre-Raphaelites carried the mantle of Romanticism to more specific ends. Their work embodied a deep sincerity, with heartfelt observations on grave topics.

Their work was detailed, with fastidious detail given to every leaf and blade of grass. They loved to depict strikingly difficult subject matter: flowing hair, dresses, and the interplay of light and water.

In an effort to recapture the bright colors of the Renaissance, they created new techniques — going above and beyond their inspiration. Over a white wet layer, they applied vanishing layers of glaze. This is what gives their work the haunting, glowing quality that they are renowned for today.

The Brotherhood went public after a year of secrecy, but by 1854 the group disbanded. In that handful of years, they produced some of the most etheric, mesmerizing works of the 19th — or any — century.

John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1852) is a striking example of this group’s powers. The theme of desperation, captured in the face of the Shakespeare character just after her suicide, is a great contrast to the verdant nature surrounding her. The dichotomy between human tragedy and the infinite grace of the natural world is masterfully presented.

7. Impressionism

Possibly the largest leap into modernity that the art world ever took, Impressionism stands as one of the great schools of the 19th century.

The technological advancement that continued to change society throughout the century eventually came to the art world, producing tubed paints with a new variety of pre-mixed colors. Those features allowed artists to travel much lighter and paint at the spur of the moment. And that’s exactly what these artists began to do.

Their works were rejected multiple times by the then famous Salon de Paris, Paris’ most renowned art exhibition. Undeterred by this, the young painters including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and later Paul Cézanne amongst others, established the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs. This new group held exhibitions for their members, a major fracture in the Parisian art scene.

The Impressionists focused almost entirely on plein-air (painting sweeping scenes outdoors), working to grasp the visual essence of the scene, not every detail. They focused on the qualities of light and unexpected color, all rendered in clearly visible brush strokes, a strong contrast with the Neoclassicists.

Because of their simplified style, they focused more on pure color relationships, leading to advances in color theory and, eventually, the myriad of expressionist work to come in the next hundred years.

Painters like Claude Monet obsessed over the change of color depending on light and atmospheric conditions. His Haystacks series is a notable example of this. The work he produced continues to delight us, in part because of the ability to capture sophisticated observations of the world in an economy of detail.

8. Post-Impressionism

The popularity of Impressionism provoked a backlash, given its typically vague visual features and serene palette. A new generation of painters wanted to explore their own visual styles while maintaining the experimentation of the Impressionists.

These post-Impressionists do not make up a unified school, and in fact any two of them are likely to be very different. However, what links them is their exploration of new, inventive styles and many of the features of Impressionism and Romanticism: exploration of new subject matter, painting on the go, and deep consideration of formal experiments.

Of all the post-Impressionists, Vincent Van Gogh is by far the most well-known. His prolific career saw the crystallization of a personal style that has made him one of the most beloved artists of all time.

Over the 1880’s especially, he produced incredible, varied work with a one-of-a-kind style, like The Potato Eaters (1885), Café Terrace at Night (1888), The Night Café (1888), The Starry Night (1889), and many more. The variety of subjects is brought together by the singularity of his artistic vision — a notion of individuality you might call romantic.

9. Realism

Presaging the left-wing movements of social realism in the 20th century, 19th century French Realism sought to show life as it really was for the majority of people.

After yet another revolution in 1848, French painters turned to the common experiences of everyday people for their subject matter — creating one of the most radical departures for art, even if their techniques were fairly straight forward.

Not concerned with scenes of myth, epics, nor the portraits of “great men,” the Realists made masterpieces out of scenes of labor, burials, and the home life of peasants and the new proletariat. They were not emotionally overwrought or sentimental like the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, nor visually experimental like the Impressionists.

We see a paradigmatic example in The Stone Breakers (1849) by Gustave Courbet. It illustrates a peasant man and his son breaking rocks in stark, unemotional clarity. This is not the conquering of new lands, nor is it the beatific presence of saints. This painting shows the reality of hard struggle and the toil that was, and still is, the vast majority of human experience. By painting these kinds of scenes, the Realists highlighted the quiet dignity and profound resilience of the working masses.

10. A Transformative Heritage

The revolution of the 19th century changed the art world forever. Artists obtained more freedom to express themselves and began focusing on more abstract concepts like color and human experience. By setting off on their own impulses and insights, they opened the world up to new possibilities.

While the 20th century saw even more extreme experimentation, this never could have been imagined, much less accomplished, without the incredible legacy of beauty left by the art of the previous century.

Get updates about our next sales and exhibitions

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.